Side effects of Accessibility

- accessibility

- seo

- wcag

Introduction

The development of technology in this millennium has been rapid, and an increasing number of digital services have moved online. Amid crises like the coronavirus pandemic, the significance of digital services has further increased (The European Commission, 2023). With this growth, there is a risk that some segments of the population may be left behind.

According to the fundamental principle of the Internet, it should be accessible to all individuals (Yang, 2019). The Internet is particularly useful for people with physical limitations. For these individuals, conducting transactions from home may feel easier than traveling to access services. Well-designed and implemented web services should be accessible to everyone (Henry, 2023a). Accessibility aims to enable the use of web services for individuals with disabilities or limitations. However, not all services are accessible, placing some users at a disadvantage. Modern web services may be developed as visual spectacles, often neglecting usability and accessibility. As a result, their use is not easy or even possible for all users. Usability aims to create a user-friendly experience regardless of the user's abilities. Both accessibility and usability strive to address similar issues, which is why it is important to examine how they influence each other.

Users often navigate online through search engines (Baye et al., 2016). For users to find websites easily, they need to appear in search engine results. Search engine optimization is a technique aimed at improving the visibility of a web service in search results by using various internal and external techniques (Sharma et al., 2019; Shahzad et al., 2020). These techniques aim to optimize the content and structure of the web service to improve its ranking in search results. Both accessibility and search engine optimization aim to make content understandable and available to both users and search engines. Therefore, they have been found to have similarities and even bring benefits to each other.

In many countries, legislation is based on the international Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) developed and maintained by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) (Kevin et al., 2023). There are prejudices associated with web content accessibility guidelines. Companies may assume that they are not needed because their current customer base mostly does not consist of disabled individuals (Schmutz et al., 2016). Some companies may fear that accessibility only brings negative impacts and additional costs (Ellcessor, 2014; Richards and Hanson, 2004). However, accessibility is not only beneficial to disabled individuals. Accessibility also facilitates interaction with digital services for temporarily disabled or otherwise functionally limited individuals (Kulkarni, 2019; Henry, 2023a). Accessibility should therefore be a priority for those aiming to provide high-quality web services to as wide a customer base as possible. Such web services also enable other intangible benefits (Rush, 2018), such as a larger market reach, good usability, and improved search engine optimization.

In this article, we specifically examine these intangible benefits, which we refer to as the side effects of accessibility.

The Side Effects of Accessibility

The World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) and its Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI) have played a central role in promoting the access of people with disabilities to the web, both as users and creators (Sloan et al., 2006). Since 1997, WAI has increased awareness and developed guidelines for web content accessibility, enabling stakeholders to create accessible web services.

Currently, accessibility is largely a legal matter, which may not apply to all private entities. Possibly as a result, accessibility guidelines are rarely used in practice (Schmutz et al., 2016). Stakeholders believe that accessibility guidelines are not beneficial or may even have negative consequences for non-disabled users. Accessibility may thus be seen as a cost, with no added value to businesses among stakeholders (Ellcessor, 2014). The benefits of web content accessibility guidelines are often not seen until they are proven to bring economic benefits to a company (Richards & Hanson, 2004). Although awareness has increased, the primary challenge for web content accessibility remains their effective and appropriate implementation, as well as determining the required level of accessibility (Sloan et al., 2006).

Accessible web services enable a larger user group. According to the European Commission, there are approximately 100 million people with some form of disability within the European Union alone (The European Commission, 2023). However, producers of web services may doubt the added value of accessibility (Peters & Bradbard, 2010). They may argue that accessibility entails more costs than potential additional sales resulting from an expanded market. Nevertheless, intangible benefits such as avoiding negative publicity, improving general usability, and better rankings in search engine results should also be considered. These are what we refer to as the side effects of accessibility.

Usability

The boundary between accessibility and usability may be blurry in the same context. While accessibility aims to provide equal opportunity for people with disabilities to interact with digital services, what exactly is meant by usability?

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) defines usability in standard ISO 9241-11 as follows: "The effectiveness, efficiency, and satisfaction with which specified users achieve specified goals in particular environments" (ISO/TC 159/SC 4, 2018). From the perspective of digital services, according to ISO's definition, the goal is to maximize the user's efficiency and satisfaction in operating the service.

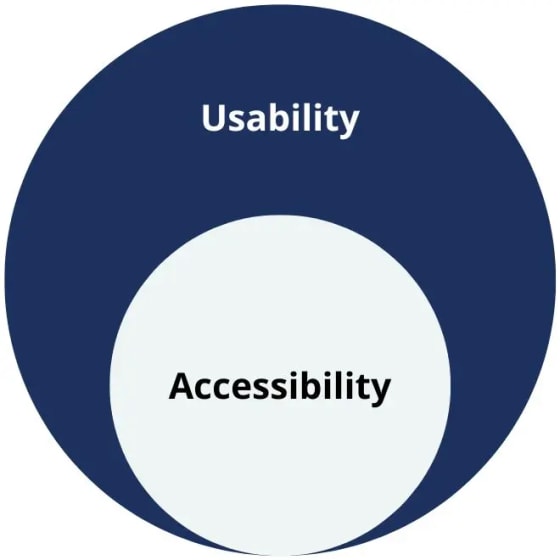

However, a usable digital service should also be understandable, learnable, functional, and appealing to all its users (Yang, 2019). There are also several other definitions of usability. These different definitions provide an understanding of a broader user group than just users with disabilities or limitations (Figure 1). In the context of this article, a digitally serviceable service is easy to use for both people with disabilities and those without any disability or limitation.

Figure 1 Usability serves a larger group of users than accessibility.

How Accessibility Benefits Usability

Although accessibility may be perceived as important only for people with disabilities, it is also beneficial to examine the issue from the perspective of all users. Neglecting user needs and resulting poor usability is one of the biggest factors affecting user numbers and user errors in services (Bevan et al., 2007). Therefore, it is particularly important for web services to be user-friendly and to consider usability if high penetration and user numbers are desired.

A web service that is largely accessible aims to adhere to accessibility principles and the level AA of web content accessibility guidelines. Such a web service includes a consistent heading structure, operability with keyboard only, user-guiding error messages, a simple layout, sufficient color contrast, and text alternatives for non-text content.

It is evident that all users benefit from web content accessibility guidelines. Especially, one large and growing user group is the aging population (Andrew et al., 2019; Richards & Hanson, 2004). Elderly individuals benefit from easier-to-read content, reduced cognitive load, less visual disturbance, and other benefits brought by accessibility. Poor lighting conditions, small screens, and suboptimal viewing angles also impair reading and navigation abilities among young users. Better readability is particularly useful for those with cognitive issues such as memory problems and attention disorders.

Obvious usability issues relate to small font sizes and color combinations that hinder readability (Richards & Hanson, 2004). Also, elements that require coordination in mouse usage or have too small clickable areas pose problems for all users. Modern web services may use decorative background images or videos, reducing the visibility of overlapping text. Producing sufficient contrast may potentially compromise the visual appearance of the page, leading to problems being overlooked.

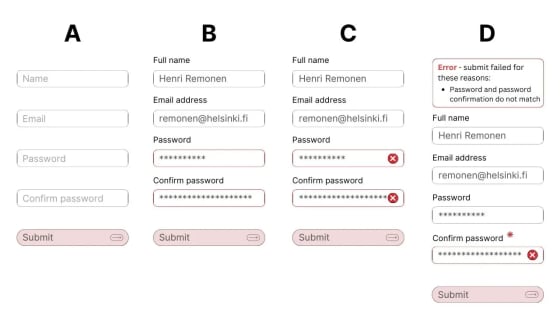

Figure 2 The many levels of the accessible online form. Form A (worst) has no field labels, Form B shows errors in a plain color, Form C has no text to explain errors and Form D (best) shows errors in color, with icons and user-guided text.

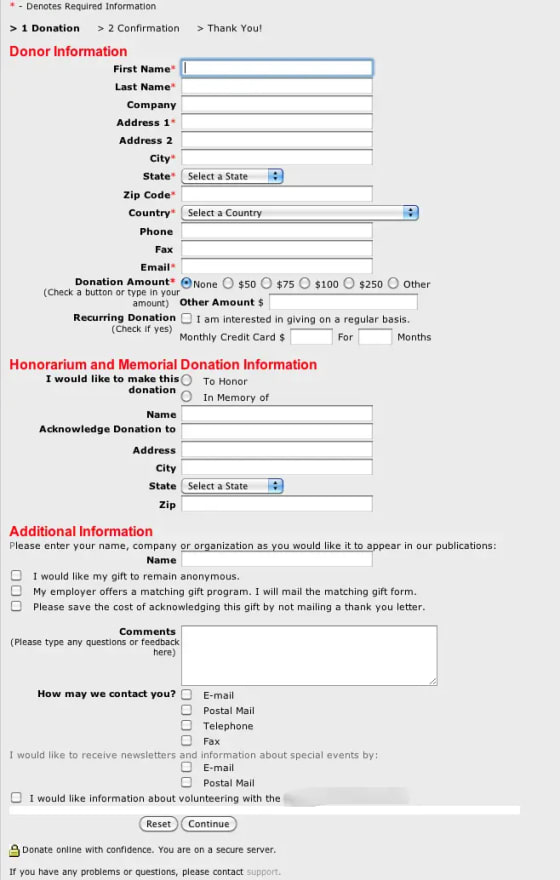

Certain issues may manifest differently in accessibility and usability. An illogical heading structure and erratic text are problematic for both accessibility and usability. From an accessibility perspective, missing field labels in a web form (as shown in Figure 2 form A) prevent the form from being filled out entirely for users of screen readers, as the screen reading software may not recognize the purpose of the field to be filled. In a web form with poor usability, such as the one shown in Figure 3, there are too many different sections, increasing the cognitive load for the user.

Figure 3 A form with poor usability has too many items, which increases the cognitive load on the user. The red color of the form also signals errors, even though there are none.

Accessibility is often approached as a technical problem, easily forgetting its human aspect (Henry et al., 2016). Usable accessibility emphasizes the integration of web content accessibility guidelines, accessibility principles, and user-centered design principles. It requires involving disabled individuals throughout the design process to ensure their needs are understood and accommodated. While compliance with standards like web content accessibility guidelines is crucial, usability processes and user involvement are equally important in creating digital services that work well for all users. Standards provide frameworks for addressing many different issues and ensure that accessibility is considered from the outset rather than as an afterthought. By combining both approaches, web designers and developers can create an equitable digital experience for all users.

In their study, Yeliz Yesilada and Harper (2015) interviewed over 300 individuals with 33 questions regarding the correlation between accessibility, user experience, and usability. Respondents felt that usability is highly dependent on accessibility and that accessibility benefits all users. However, they did not consider good usability alone sufficient to guarantee adequate accessibility. Similarly, Yang (2019) in his study found that generally, websites with higher accessibility scores also received significantly higher usability scores. Although the study focused solely on homepages, it was noted that homepages create the first impression for users, and the overall usability or accessibility level does not improve on other pages. Improving the accessibility of websites benefits all users, as the side effects of accessibility improvements result in higher usability.

Search Engine Optimization

Search engines cannot interpret multimedia content such as images, videos, or audio recordings in the same way humans can (Ellcessor, 2012). Accessible web services help search engines understand their content, improving their ability to interact with them (Ferraz, 2015). Currently, search engines utilize metadata from multimedia and, for example, non-text content alternatives familiar from accessibility. These enable search engines to index and present multimedia content in their search results (Google, 2024b).

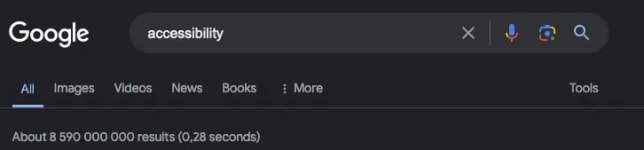

Figure 4 Google search results for the keyword accessibility

The role of search engines in reaching users is significant. Search engines serve as the primary way for users to gather information online (Baye et al., 2016). When users search for information, they input a search query or keyword into the search engine, which attempts to provide the most suitable results from indexed websites (Sharma et al., 2019). For instance, Google offers around 8 590 million indexed search results for the keyword "accessibility" as shown in Figure 4 (Google, 2024b). Direct traffic to websites from search results is called organic traffic. Search engines also provide paid sponsored search results. However, traffic from these search results is not considered organic because the place in the search results is achieved by payment. Nonetheless, most of the user-generated traffic is organic traffic. Maximizing a website's ranking in search results and the organic traffic it brings is pursued through a method called search engine optimization (SEO) (Baye et al., 2016; Sharma et al., 2019).

Merely publishing a webpage does not guarantee its inclusion in search engine indexes or its appearance in search results. For instance, Google guides how to get a webpage indexed (Google, 2024a). Search engine optimization is the next step after a webpage has been indexed.

Over 90 percent of search engine users do not look beyond the first ten search results, and up to 63 percent of users only view the first three search results (Sharma et al., 2019). Therefore, it is crucial to rank within the top ten search results. Increased visibility among users helps attract more traffic to a website, subsequently growing business.

The Factors Affecting Search Engine Optimization

The factors influencing search engine optimization can be roughly divided into two categories: on-page search engine optimization and off-page search engine optimization (Shahzad et al., 2020).

Figure 5 On-page search engine optimization is influenced by the structural elements of the page, such as headings, content, and images. Off-page search engine optimization is influenced by external elements, such as return links from other pages, media advertising, and social media presence.

On-page search engine optimization focuses on the content and structure of the website (Shahzad et al., 2020). It can be thought of as being in the hands of developers (Sharma et al., 2019). Figure 5 visualizes the factors influencing on-page search engine optimization within the area delineated by the dashed line. These include textual content, headings, links, navigation structures, images and image captions, and similar elements. These aspects must be also well-maintained with accessibility, usability, and user experience in mind.

On the other hand, off-page search engine optimization deals with how other sources refer to the website (Shahzad et al., 2020). Contrary to on-page factors, these aspects are not within the control of developers (Sharma et al., 2019). Figure 5 visualizes the factors influencing off-page search engine optimization outside the area delineated by the dashed line. Off-page search engine optimization can be influenced by being active and sharing content, creating social media accounts, submitting the website's sitemap to search engines, advertising on social media, and other similar manual "marketing" efforts (Shahzad et al., 2020; Sharma et al., 2019; Google, 2024b).

Search Engine Optimization Techniques

The techniques of search engine optimization are largely categorized into practices that are recommended for use, known as white hat techniques, and those that are not recommended for use, known as black hat techniques. Table 1 provides a summary of the differences between search engine optimization techniques.

| White hat SEO | Black hat SEO |

|---|---|

| The recommended way to do search engine optimization. | Not a recommended way to do search engine optimization. |

| Use and follow the guidelines and rules provided by search engines. | Breaks guidelines and rules, trying to find weaknesses in them. |

| Produce a gradual sustainable improvement in search rankings. | May temporarily increase rankings in search engines. |

| Achieved by producing quality content where keywords are used in a rational way in the content, by continuously developing the site and its structure, and by regularly publishing good content. | Artificially tries to make a site look relevant and trustworthy using various techniques. As a result, search engines may ban sites that use these techniques. |

Table 1: Comparison of search engine optimization techniques.

White hat search engine optimization techniques are the most important and well-known (Shahzad et al., 2020). Their purpose is to improve the visibility of a website using permissible techniques and methods to enhance visibility in search results. White hat techniques adhere to guidelines and rules provided by search engines (Sharma et al., 2019). These methods include high-quality content, keyword research and analysis, email campaigns, submitting sitemaps to search engines, and improving and developing website structure. Using white hat techniques is slow and gradual, but it brings long-term growth in search result rankings.

Black hat search engine optimization techniques are the opposite of white hat techniques (Sharma et al., 2019). They aim to exploit questionable and prohibited techniques to enhance the visibility of a website in search results (Shahzad et al., 2020). Black hat techniques exploit weaknesses in search engines and do not comply with the guidelines and rules provided by search engines. These include unnecessary repetition of keywords and links in the content, purchased links from other websites, displaying different content to search engines than to users, and hidden links and content. Using these techniques may bring quick but not lasting growth in search result rankings.

How Accessibility Aids with Search Engine Optimization

From a business perspective, it is crucial for a company's web services not only to appear in search results but to rank higher than its competitors (Moreno López & Martínez Fernández, 2013). A higher ranking in search results increases the likelihood of users visiting the site. As mentioned earlier, the role of search engines is significant in reaching users, and most users choose an option from the first three search results.

Both search engine optimization and accessibility aim to make web content easily understandable, available, and convey the same content to all users. Web services that are difficult to navigate pose a problem for accessibility but also affect the ability of search engine crawlers to navigate content. Search engines can index accessible websites more efficiently than those that are not accessible (Peters & Bradbard, 2010). This was also noted in the study by Moreno López and Martínez Fernández (2013) when accessible websites consistently appeared at the top of search engine results without intentionally using search engine optimization techniques.

An examination of web content accessibility guidelines and search engine optimization techniques reveals that they are very similar and overlap (Moreno López & Martínez Fernández, 2013). Many accessibility requirements ensure that the web service has a good structure, such as a logical heading structure, text alternatives for non-text content, and descriptive link texts. Search engines also benefit from these, especially when they cannot understand the purpose of images otherwise (Ferraz, 2015). It can be thought of that a search engine robot is essentially a blind user navigating the web page in the same way as a visually impaired person would with a screen reader (Ellcessor, 2012; Moreno López & Martínez Fernández, 2013). Text alternatives must be descriptive so that a visually impaired person can perceive the image and the search engine robot can index it in search results. Similarly, the search engine robot utilizes descriptions of videos and audio recordings for indexing, much like a hearing-impaired person would use them to understand the content of the video.

Other Benefits Beyond Usability and SEO

Accessible web content brings not only usability and search engine optimization benefits but also other intangible advantages. These benefits include promoting innovation, enhancing brand reputation, expanding market reach, and minimizing legal risks (Rush, 2018). Accessible web content can also give companies a competitive edge over their rivals (Leitner et al., 2016). As a side effect, improved usability facilitates interaction with services, especially for the aging population. In the study by Leitner et al. (2016), some respondents saw this as the primary motivation for producing accessible web services.

Commitment to accessibility demonstrates genuine corporate social responsibility (Rush, 2018). Considering stakeholders' needs and acting accordingly offers many benefits, such as improving image, reputation, and customer loyalty. Also, how customers perceive the company affects customer loyalty (Leitner et al., 2016). These benefits are closely linked to the profitability of the company; for example, a negative image can harm the company's brand and business. People's perceptions of companies are much more sensitive to negative than positive publicity, which is why companies strive to avoid negative publicity by all means (Peters & Bradbard, 2010). Social aspects such as equality, ethics, and responsibility can also be assets for companies that implement accessible services. Many people believe that the benefits of accessibility legislation outweigh the additional costs for companies. Accessibility thus seems to be a societal issue supported by many, which in turn can affect people's views of the company. It would be an interesting contradiction if a company appeared to be in favor of equality but their web services were not accessible.

Accessible websites are usually of higher quality than inaccessible ones (Leitner et al., 2016). The use of navigations, headers, correct heading levels, and lists promotes the quality, structure, and appearance of the site. Web content accessibility guidelines contain many improvements that also result in better code. At the core of accessibility technically are semantic HTML elements, which represent specific functionality. For example, the <h1> element represents the main heading of the page, <nav> represents navigation, and <footer> represents the footer of the site. Implementing web content accessibility guidelines also brings tangible cost savings (Peters & Bradbard, 2010). Many organizations have found that an accessible web service is easier to maintain and of higher quality than the previous inaccessible version. Maintenance of the site is also reduced when there is no need to create multiple versions for different devices or older software.

Conclusion

Accessibility primarily focuses on users with disabilities or limitations. However, many of the accessibility guidelines for web content also bring benefits to all users. These examples were examined as side effects of accessibility. It is important, therefore, that accessibility be seen as beneficial to everyone and that accessible services be created regardless of legal obligations.

The article reveals that accessibility also enhances the usability of web services. Usability is a matter that concerns all users, not just those with disabilities or limitations. Particularly, the aging population benefits from accessibility. Elderly individuals often face cognitive issues that accessibility addresses. The elderly may also be constrained in accessing services physically, hence web services need to be usable for them.

Accessibility also brings benefits to search engine optimization of websites. Many techniques of accessibility and internal search engine optimization are similar. Thus, following web content accessibility guidelines also improves search engine optimization without specifically aiming for it. A search engine crawler can be thought of as a user needing accessible content, as it does not use a mouse or a screen, so it must be able to navigate and interact with web services in other ways.

Accessible web services have many other impacts as well. The article observed accessibility bringing social impacts such as improved image and customer loyalty. Commitment to accessibility positively communicates a company's social responsibility and values to customers. Organizations can also benefit from accessibility in the form of higher-quality source code. Quality source code means less need for maintenance, resulting in reduced upkeep requirements.

However, the purpose of the article is not to diminish the importance of accessibility and its ultimate goal; to create an equal experience for users with disabilities. The aim is to dispel prejudices that accessibility could not also benefit others. If private and public actors are convinced that improving the accessibility of web services and adhering to web content accessibility guidelines could also benefit all users, they would have a greater interest in promoting and investing in accessibility in their services.

Bibliography

-

Andrew, K., Connor, J. O., Alastair, C., and Michael, C. (2019). Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.1. [Referenced 23.1.2024]. url: https://www.w3.org/TR/WCAG21/

-

Baye, M. R., De los Santos, B., and Wildenbeest, M. R. (2016). “Search Engine Optimization: What Drives Organic Traffic to Retail Sites?” In: Journal of Economics & Management Strategy 25.1, pp. 6–31. doi: 10.1111/jems.12141

-

Bevan, N., Petrie, H., and Claridge, N. (2007). “Improving Usability and Accessibility”. In: Proceedings of IST Africa

-

Ellcessor, E. (2012). “Captions On, Off, on TV, Online: Accessibility and Search Engine Optimization in Online Closed Captioning”. In: Television & New Media 13.4, pp. 329–352. doi: 10.1177/1527476411425251

-

Ellcessor, E. (2014). “

<ALT=“Textbooks”>: Web Accessibility Myths as Negotiated Industrial Lore”. In: Critical Studies in Media Communication 31.5, pp. 448–463. doi: 10.1080/15295036.2014.919660 -

Ferraz, R. (2015). “Exploring web attributes related to image accessibility and their impact on search engine indexing”. In: Procedia Computer Science 67, pp. 171–184. doi: 10.1016/j.procs.2015.09.261

-

Google (2024a). Google Search Essentials. [Referenced 19.3.2024]. URL: https://developers.google.com/search/docs/essentials

-

Google (2024b). Search Engine Optimization (SEO) Starter Guide. [Referenced 7.2.2024]. URL: https://developers.google.com/search/docs/fundamentals/seo-starter-guide

-

Henry, S. L. (2023a). Introduction to Web Accessibility. [Referenced 23.1.2024]. URL: https://www.w3.org/WAI/fundamentals/accessibility-intro/

-

Henry, S. L. (2023b). Evaluating Web Accessibility Overview. [Referenced 6.2.2024]. URL: https://www.w3.org/WAI/test-evaluate/

-

Henry, S. L., Abou-Zahra, S., and White, K. (2016). Accessibility, Usability, and Inclusion. [Referenced 31.1.2024]. URL: https://www.w3.org/WAI/fundamentals/accessibility-usability-inclusion

-

ISO/TC 159/SC 4 (Mar. 2018). Ergonomics of human-system interaction — Part 11: Usability: Definitions and concepts. en. Standard ISO/TC 159/SC 9241-11:2018. Geneva, CH: International Organization for Standardization. url: https://www.iso.org/standard/63500.html

-

Kevin, W., Britt, C., Michel, H., Vera, L., and Eric, V. (2023). Web Accessibility Laws I& Policies. [Referenced 23.1.2024]. url: https://www.w3.org/WAI/policies/

-

Kulkarni, M. (2019). “Digital accessibility: Challenges and opportunities”. In: IIMB Management Review 31.1, pp. 91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.iimb.2018.05.009

-

Leitner, M.-L., Strauss, C., and Stummer, C. (2016). “Web accessibility implementation in private sector organizations: motivations and business impact”. In: Universal Access in the Information Society 15, pp. 249–260. doi: 10.1007/s10209-014-0380-1

-

Moreno López, L. and Martínez Fernández, P. (2013). “Overlapping factors in search engine optimization and web accessibility”. In: Online Information Review 37.4, pp. 564–580. doi: 10.1108/OIR-04-2012-0063

-

Peters, C. and Bradbard, D. A. (2010). “Web accessibility: an introduction and ethical implications”. In: Journal of Information, Communication and Ethics in Society 8.2, pp. 206–232. doi: 10.1108/14779961011041757

-

Richards, J. T. and Hanson, V. L. (2004). “Web accessibility: a broader view”. In: Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on World Wide Web. WWW ’04. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, pp. 72–79. doi: 10.1145/988672.988683

-

Rush, S. (2018). The Business Case for Digital Accessibility. [Referenced 14.2.2024]. URL: https://www.w3.org/WAI/business-case/

-

Schmutz, S., Sonderegger, A., and Sauer, J. (2016). “Implementing Recommendations From Web Accessibility Guidelines: Would They Also Provide Benefits to Nondisabled Users”. In: Human Factors 58.4, pp. 611–629. doi: 10.1177/0018720816640962

-

Shahzad, A., Jacob, D. W., Nawi, N. M., Mahdin, H., and Saputri, M. E. (2020). “The new trend for search engine optimization, tools and techniques”. In: Indonesian Journal of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science 18.3, pp. 1568–1583. doi: 10.11591/ijeecs.v18.i3.pp1568-1583

-

Sharma, D., Shukla, R., Giri, A. K., and Kumar, S. (2019). “A Brief Review on Search Engine Optimization”. In: 2019 9th International Conference on Cloud Computing, Data Science Engineering (Confluence). IEEE, pp. 687–692. doi: 10.1109/CONFLUENCE.2019.8776976

-

Sloan, D., Heath, A., Hamilton, F., Kelly, B., Petrie, H., and Phipps, L. (2006). “Contextual web accessibility - maximizing the benefit of accessibility guidelines”. In: Proceedings of the 2006 International Cross-Disciplinary Workshop on Web Accessibility (W4A): Building the Mobile Web: Rediscovering Accessibility? W4A ’06. Edinburgh, United Kingdom: Association for Computing Machinery, pp. 121–131. doi 10.1145/1133219.1133242

-

The European Commission (2023). Shaping Europe’s digital future. [Referenced 23.1.2024]. URL: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/web-accessibility

-

Yang, B. (2019). “The relationship between website accessibility and usability: an examination of us county government online portals”. In: Electronic Journal of e-Government 17.1, pp47–62

-

Yeliz Yesilada Giorgio Brajnik, M. V. and Harper, S. (2015). “Exploring perceptions of web accessibility: a survey approach”. In: Behaviour & Information Technology 34.2, pp. 119–134. doi: 10.1080/0144929X.2013.848238.