How to Start Fostering the Accessibility Tree

- accessibility

- html

Understanding the DOM is paramount for comprehending the accessibility tree, as it forms the foundation upon which the tree is built. The DOM acts as the backbone of web development, providing a structured representation of web pages that browsers can interpret and users can interact with. This structured representation forms the basis for the Accessibility Tree.

What is the Document Object Model?

The DOM is a programming interface (API) for web documents. DOM represents the structure of a document as a tree of objects. Each object corresponds to a part of the document in the tree. It provides a way to interact and manipulate the content, structure, and style of a web page in real-time.

How is the Web Page Rendered

The process of interacting with a web page:

-

The browser requests the web page over HTTP from the server.

-

The browser parses the HTML. Links referring to a style sheet and scripts in the HTML results in the browser requesting those from the server.

-

The browser generates a DOM tree of the web page, generates a CSSOM structure from the CSS, and executes the JavaScript.

-

A visual representation of all of this is displayed to the end user’s screen.

The browser updates the DOM as the application runs, which is then displayed to the user’s display ready to be interacted with a mouse and a keyboard.

Mouse and a keyboard? Yes, this is not the ideal structure for assistive technologies. User using assistive technology needs a different structure that they can interact with.

What is the Accessibility Tree

The model used by assistive technology is called an accessibility tree. An accessibility tree is a derivative of the DOM tree. They are not the same thing, nor are they structurally exact. However, they coexist.

The accessibility tree excludes any non-semantic elements, such as

Diving deeper, the accessibility tree is used by the platform-specific Accessibility APIs to provide representation of the application understood by assistive technologies.

Accessible Objects as the Foundation

The accessibility APIs provides accessible objects for applications to use. These objects are bundles of properties that represent the functionality of a UI element in the application.

You could visualize the accessible objects as components. Each component represents single functionality and by creating multiple components we get the whole application.

The components have different attributes that convey information about it:

Name and description.

Components accessible name and description. Screen readers use the accessible name to announce an object. Based on the accessible name, some users might target specific objects.

Role

Main indicator of the objects type, like a button or checkbox. Role is used by tools and assistive technologies to present and support interaction with the object consistently with user expectations.

State

Components dynamic property. A value that may change in response to user interaction or automated process. States are expected to change often, like information if a checkbox is clicked. States do not affect the nature of the object, but convey data associated with the object.

These components are used but not limited to web applications. The idea of these components is to have a standardized method of describing information for assistive technologies regardless of the underlying applications type.

How the User Interacts with the Accessibility Tree

We already covered how a web page is rendered to a user ready to be interacted with a mouse and a keyboard.

Users that are using assistive technology need it different. Not from the users’ point-of-view, but the systems point of view things has changed.

The process of interacting with a web page for an assistive technology user is something in the following line:

-

The browser requests the web page over HTTP from the server.

-

The browser parses the HTML. Any links referring to a style sheet and scripts in the HTML will result the browser requesting those from the server.

-

The browser generates a DOM tree of the web page, generates a CSSOM structure from the CSS, and executes the JavaScript. Parallel to the DOM a accessibility tree is created. NOTE: the accessibility tree is created regardless of the user using assistive technologies.

-

A visual representation of all of this is displayed to the end user’s screen. This means that the user could also interact with traditional methods, using a mouse and a keyboard.

-

Accessibility API interacts with the accessibility tree and augments the UI with needed information.

-

Assistive technologies can interact with the web page through the accessibility API.

Now the epicenter has shifted from the DOM to the accessibility tree and the accessibility API. Now the ball is in the developer’s court. The software must be built so that it is accessible, meaning that it must be built so that the tree can be created from the existing DOM.

Accessibility Tree Helps to Build Quality Software

Accessibility tree forces to think about how the software is perceived. It removes any non-semantic elements and styling. Being aware of the accessibility tree guides us to build quality software.

As we found out, the accessibility tree is the only way assistive technology can interact with our web page. We must take care that the tree is in mint condition. Thankfully, we have tools at our disposal that will help us groom and build the tree. Semantic HTML and using ARIA.

Semantic HTML Builds Accessibility Trees

Semantic HTML provides semantic information about the elements. It is the most straightforward method to provide accessible user experience.

Accessibility for semantic HTML elements is handled automatically. The browser will identify the semantic information and build the corresponding accessibility tree for us with minimal effort. That is why it is paramount for accessibility to use the semantic HTML elements when possible.

What the Accessibility Tree Looks Like

Imagine a web page prompts user the terms of service consent using the following non-semantic markup:

<!doctype html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8" />

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1.0" />

<title>Terms of Service</title>

</head>

<body>

<div class="container">

<div class="header">Terms of Service</div>

<div class="content">

<div>Text containing the terms...</div>

</div>

<div class="button-container">

<span class="accept-btn">Accept</span>

<span class="decline-btn">Decline</span>

</div>

</div>

</body>

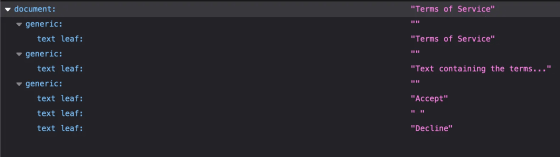

</html>The markup produces the following accessibility tree:

Accessibility tree of non-semantic HTML elements

It looks like a tree, but it is not a very helpful tree. All the elements are just generic text leaves that do not provide any accessible meaning to the users that would need them to interact with the page.

Now, if the same page was to be developed using semantic elements:

<!doctype html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8" />

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1.0" />

<title>Terms of Service</title>

</head>

<body>

<article>

<header>

<h1>Terms of Service</h1>

</header>

<section>

<div>Text containing the terms...</div>

</section>

<footer>

<button>Accept</button>

<button>Decline</button>

</footer>

</article>

</body>

</html>As a result, we get a more healthy-looking accessibility tree:

Accessibility tree of semantic HTML elements

Now the accessibility tree contains information about the elements. Assistive technologies can interact with the web page correctly thanks to the informative accessibility tree.

These two examples could’ve been developed to look and function the same using CSS and JavaScript. However, without using ARIA, the

Sometimes web pages include information that is hidden with CSS styles. It is good practice to verify the accessibility tree for elements that should’ve been hidden from assistive technologies. Elements that should’ve been hidden but are not might lead to exhaustive experience of the users using assistive technologies. It is smart to check the accessibility tree to fix such oversights and to implement adequate techniques for hiding elements.

ARIA Helps with Dynamic Content

Sometimes there is no semantic element to describe a specific widget. In which case, we must provide a way for assistive technologies to identify the widget using WAI-ARIA. WAI-ARIA communicates semantic information to assistive technologies by building accessible objects out of non-semantic elements. I will be covering WAI-ARIA in the next post, but it is important to acknowledge the possibility now.

It is advisory to stick to semantic HTML elements as long as possible. Providing incorrect ARIA semantics can lead to an accessibility mess, and you’ve just made the tree a hell. There is a saying that no ARIA is better than bad ARIA.

For the time being. ARIA Authoring Practices Guide provides extensive information about how to make non-semantic widgets accessible.